Ages ago, I applied for a software developer job, and after a short briefing the recruiter sent me a link to an MBTI profiling service. I smiled and politely rejected the opportunity.

Most engineers I know laugh at pseudo-scientific "psychological" profiling like MBTI / DISC, and laugh even harder at folks who use astrology or tarot card readings to decide whether a candidate will be a good match.

Good engineers are trained to operate within the scientific method. The scientific method demands that experiment results are reproducible and reliable. If the experiment's results are reliable, there is a higher chance that the hypothesis is correct.

With astrology, MBTI / DISC, tarot card readings and other pseudo-scientific methods the results are unreliable. We simply cannot trust them; their value is zero.

Some engineers go further and question other processes within hiring. For instance, they run experiments to see the reliability of their recruiters’ judgements based on reading CVs. These engineers want to understand whether recruiters are actually bringing good candidates to the interview stage (and filtering out "bad" candidates).

In the previous article, I mentioned a case from my experience where almost 400 hours within a year were spent on interviews with the result of hiring only 35 engineers, and suggested some ways to analyse and improve the efficiency of the overall hiring process. TL;DR: the more good candidates are brought to the interviews, the less time we waste, the more efficient the process is.

In this article, I want to focus on the interviews. While engineers laugh at astrology, many of us, frankly speaking, still rely on interview methods with very similar reliability.

Interviews as tests: reliability and validity

In engineering, tests are only useful if they have at least two properties: reliability and validity. Reliability means that when the same system is tested multiple times, the result is stable. Validity means that the test result actually tells us something meaningful about the property we care about.

A test that gives random results is useless. A test that is reliable, but measures the wrong property, is also useless.

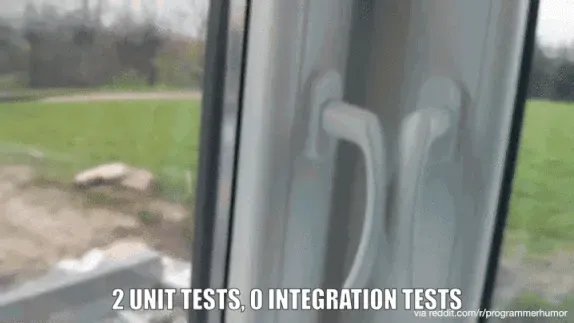

In software, a flaky test is an example of a reliability problem. Sometimes it passes, sometimes it fails, with no real change in the code. Reliable tests support our decision-making: when they fail, we know what to research; when they pass, we know we can proceed. With flaky tests, we have to invest additional effort in debugging them, or we simply ignore them.

An unreliable test actively damages decision-making by producing noise that looks like a signal.

Many interview formats are unreliable. Beyond obviously unreliable methods like MBTI, DISC, astrology or reading tarot cards, consider an unstructured "culture fit chat". The same candidate can receive completely different feedback depending on the interviewer's mood, recent experiences, or personal biases. The process might feel "human" and "natural", but objectively it is a flaky test.

The interview method might also be reliable, well structured and hard to misinterpret, but its validity might still suffer. For instance, an algorithmic puzzle can (and should) produce consistent results: if a candidate knows how to solve these puzzles, they will reliably pass the test. But does this test provide valid results for our hypothesis? In other words, how well passing this test correlates with future job performance? If most of the candidates learn by heart these particular puzzles, can we say they know how to find and solve algorithmic problems at work?

In software testing, we can also have reliable non-flaky tests which don't give valid results for whether the system works. Have you seen tests which are excessively mocked, which give you the feeling they test the mocks more, not the actual code?

Here, validity is about correlation: how well the test result correlates with the desired system behaviour. If all the tests in the suite pass, are we certain that the system works? If the suite fails, are we certain that the system doesn't behave as it should?

In software testing, we always strive to write tests which are reliable (not flaky) and valid (correlating well with the desired system behaviour).

In interview methods design, we should strive for the same goals: the interview methods should be reliable and valid.

High-correlation vs low-correlation interview methods

There are many interview formats with inherently low validity.

A common example is a loosely defined "people" part of the interview: questions about "strengths and weaknesses", "where do you see yourself in five years", and generic behavioural prompts ("tell me about a time when..."). These questions have well-known, socially acceptable answer patterns. There is also an entire industry of books, blog posts and coaching sessions focused on help in passing behavioural interviews. As a result, these conversations often mostly measure candidate's ability to perform a rehearsed script, not the ability to work effectively in this particular environment.

This means that the correlation with real performance might be very low.

These tests aren't flaky, but they don't show if the system works well.

High-correlation methods look different. They are designed around the actual work for a specific position, in a specific team, with a specific type of tasks. There is no universal "good interview format"; each team has to design its own based on what the job really requires.

Typical examples (only as examples, not a universal recipe) can be:

- a coding or debugging exercise similar to tasks from this team's codebase;

- if a team does code reviews, a code review session on a realistic change, with a discussion of trade-offs and risks;

- designing a simple test strategy or test plan for a subsystem that resembles this team’s system;

- a short architecture or design exercise close to this team's domain and real constraints.

The goal of such formats is to increase correlation so that performance in the interview is a reasonable proxy for performance in the real job. Candidates will still prepare, but preparation will involve learning skills that are actually useful for the work (reading code, reasoning about trade-offs, communicating clearly under realistic constraints), not just memorising stories and templates.

One interview format which comes close to ideal, is pair or mob (ensemble) work session. In this case, the interview is not a special artificial exercise but a short version of how the team actually works: several people looking at real or realistic code or problems together, asking questions, proposing changes, and making decisions as a group. Validity is high, because the activity in the interview is almost the same as the activity in daily work. Reliability is also higher: several interviewers observe the same behaviour at the same time and can compare their impressions afterwards, instead of relying on a single person’s intuition. Preparation for such an interview is also useful preparation: to “do well”, candidates have to practice skills that will be needed in the job (reading unfamiliar code, explaining decisions, collaborating under uncertainty), not just learning how to tell stories. However, this format only makes sense if the team really uses pair or mob work in their everyday practice.

Designing high-correlation interview methods is always local work. Each team needs to explicitly ask what kind of work is actually done in this role, and which small, practical exercises can approximate that work in an interview setting. Once such a format is designed, the next step is to verify whether it behaves like a good test. For this, existing employees can be used as a control sample.

Control samples

In software testing, a test is always written for a test object: a function, a service, an API, a system. When the test runs and passes, we assume that this object behaves according to the expectations encoded in the test. If the same test later starts failing, we know that something has changed: either the object changed and the test is now catching a real problem, or the test itself has become outdated or brittle.

To see that a new test gives us any value at all, we usually run it on an object we already understand. A known-good build should pass. A build with a known defect in this area should fail. If that does not happen, the problem is with the test, not with the code.

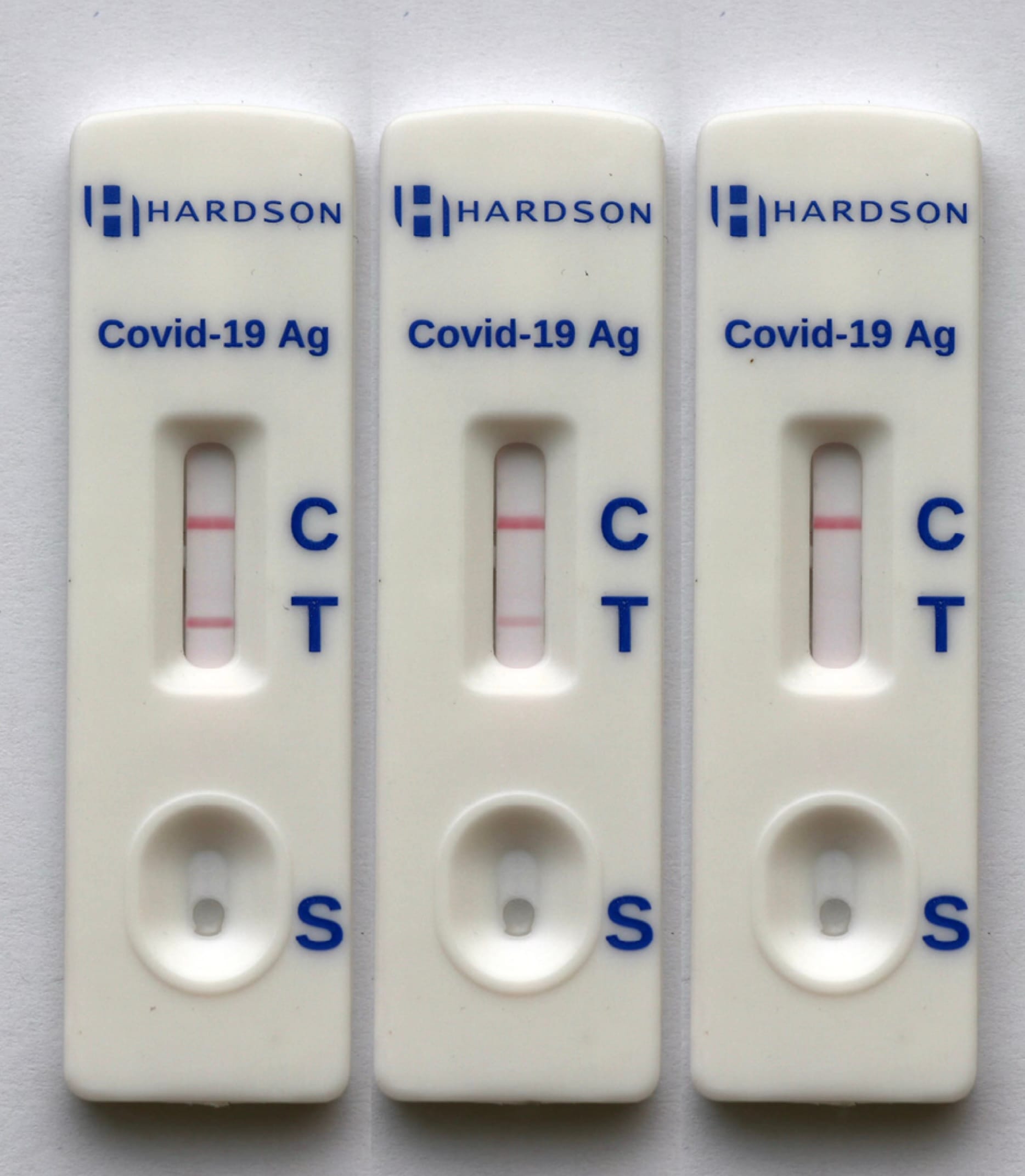

Many medical tests have this logic built in. Think of a COVID rapid test: the control line is always there to confirm that the test itself is working. If the control line does not appear, the result is invalid, regardless of what the "positive/negative" line shows. The control sample validates the test device.

In hiring, we rarely do anything similar. We introduce a new interview format and immediately start using it on candidates. If someone "fails", we tend to assume that the candidate is bad. But without a control sample we do not know whether the interview method itself is any good.

The control sample in hiring is our existing employees.

In most teams, it is not difficult to name several people who are clearly strong in the role, and sometimes one or two who are struggling. The idea is not to re-interview them to decide whether they "deserve" their job, but to use their participation to check whether the interview behaves like a reasonable measurement tool.

Strong performers should generally be evaluated as strong. People who struggle in daily work should not appear as clear "top candidates" in the interview. There can be surprises and edge cases, but if the interview systematically "fails" known good people or “passes” known weak ones, this is a signal about the interview, not about the employees.

This exercise is useful for calibration. It often reveals that a task is too ambiguous, that the scoring rubric is unclear, or that interviewers focus on different aspects and interpret the same behaviour differently. It is much cheaper to discover and fix these issues on internal people, who are not making a high-stakes career decision, than on external candidates.

Interview results and probation outcomes

Designing a high-correlation interview and validating it on existing employees is only the first step. The next step is to see how well the interview results correlate with outcomes for new hires.

In software, a test suite is judged not only by how it behaves on known-good and known-bad builds, but also by how its failures relate to incidents in production. If many production failures appear without any related test failures, the value of the test suite is low. If tests fail regularly without any visible effect on users, the tests may be misaligned. The same logic applies to interviews.

For hiring, the simplest outcome to track is probation. For each new hire, it is usually clear after several months whether they passed probation confidently and started contributing as expected, passed but with noticeable concerns or extra support, or did not pass at all (sometimes with a role change as a result). On the interview side, there is also usually some scoring: numeric scores, written ratings, or at least an internal classification such as "strong hire", "hire", "weak hire" or "no hire".

For each hire, you record the interview assessment in a structured way, ideally both the overall assessment and the scores per exercise or dimension. After probation, you record the outcome in a similarly structured way. From time to time, you review how these sets of data relate to each other.

If the interview method is sensible, strong interview results should correspond to good probation outcomes in a noticeable majority of cases. If the interview regularly classifies people as "strong hire" who then struggle in real work, or if people with "borderline" interview scores consistently become top performers, this is a sign that the method does not measure what matters.

The goal for this is to treat interview methods as tests that must prove their usefulness.

Sanity checking your interview pipeline

By this stage, we have enough information to perform a simple review of an existing interview pipeline and decide which parts are worth keeping and which ones are mostly theatre.

A practical starting point is to walk through the current pipeline step by step. For each step it is useful to write down what this step is supposed to measure. If nobody can formulate this clearly, it is already a signal. If the goal is clear, the next question is whether this step is close to the real work for this role in this team, or whether it is a generic format copied from somewhere else.

The next question is whether there is any evidence that the step measures what it claims to measure. For example, has this exercise been tried on existing strong employees, and did they demonstrate the expected behaviour? Have you ever looked at how the results of this step relate to probation outcomes, even informally? Sometimes the honest answer is “no, we never checked, we just assumed it is useful”. In that case, the step is a candidate for either validation or removal.

It is not necessary to redesign everything at once. It might be better to identify one obviously low-correlation element and reduce its impact (or even remove it), and to strengthen one element that is clearly closer to real work. You can then run this revised step once on existing employees as a control sample, and start recording its results for new hires together with probation outcomes.

Over time, you will likely see that some parts of the pipeline consistently add value, while others mainly consume time and create noise. Parts that show no visible connection to later performance, or that clearly contradict what you know about existing employees, should be treated as process bugs or waste.

Conclusion: apply QA thinking to hiring!

We don't like flaky tests in our codebase, we know they are too costly. If tests failed at random, measured the wrong things, or had no connection to production behaviour, we would fix them or remove them.

In hiring, we might laugh at MBTI and astrology, but still copy-paste "best JAVA questions" from GitHub repos to our interviews, or ask generic behavioural questions and request candidates to solve puzzles unrelated to the work.

Interviews can be treated as tests. They should be reliable, close to real work, and at least roughly correlated with probation outcomes. They should be validated on a control sample of existing employees before we use them to judge strangers.

You're a QA professional, act like one in hiring too!