Many years ago, while working for a bank, I was a member of the techleads guild. Being a guild member in large companies often comes with the responsibility to interview people, and I interviewed a lot. Sometimes I had up to twelve interviews a week. I still shudder remembering these weeks.

On average, there were 6 interviews per week, some interviews lasted up to 1.5 hours. In a year, I spent ~400 hours on interviews to hire just 35 people. The stats were quite sad: 9 out of 10 candidates failing to pass the interviews; many of them were far from passing.

At that time, I was not questioning the process; I was simply doing my part and living through the overload.

Eight years later, I’m presenting at Testing United Milan the topic “QA approaches in hiring”, where I advise people to build better hiring processes. I don’t want people to make the same mistakes I did.

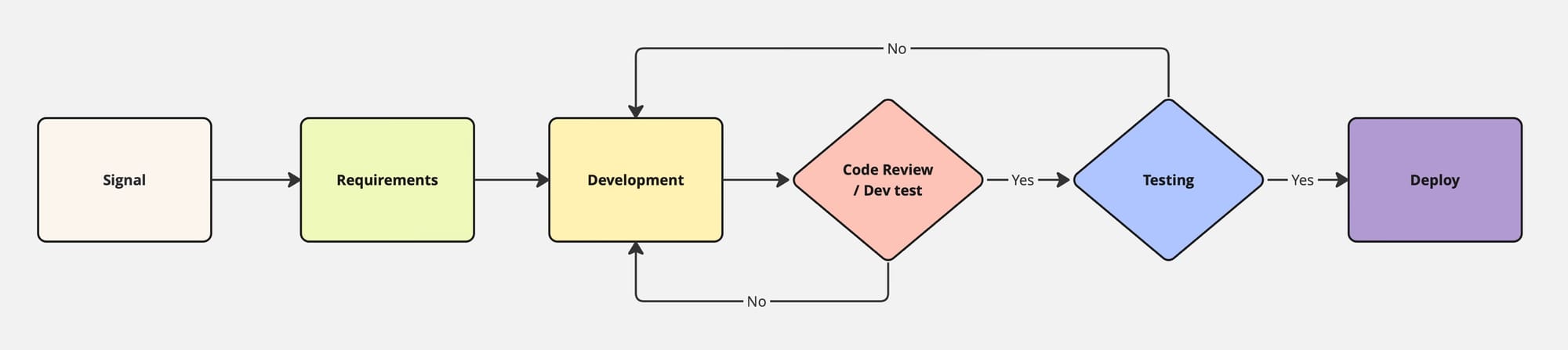

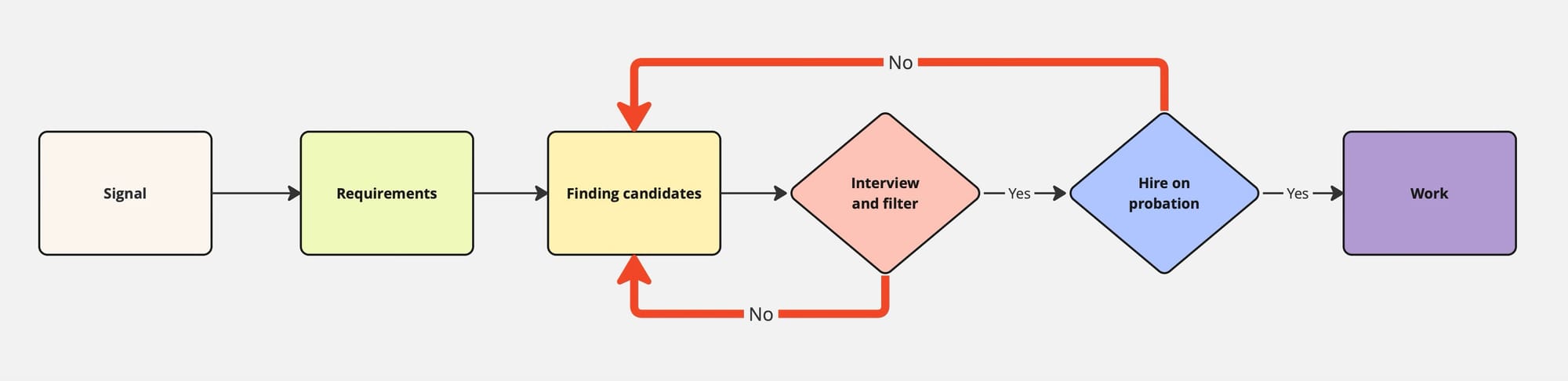

Hiring flow as a broken testing pipeline

When we look at “classical” / “waterfall” software development, testing is usually done after some artefact is created.

Imagine yourself as a tester spending 400 hours a year testing 288 features while only 35 of them are barely acceptable. You’d likely be mad. Most probably, you wouldn’t simply keep returning features back to development forever, you would start asking questions. You would be mad about the amount of rework this 288 → 35 conversion yields, you would see your testing efforts wasted.

And yet in hiring this is what was happening to me in that bank, and is still happening in many companies today: interviewers continue to conduct interviews; candidates continue to be rejected; the system continues to waste time and effort on interviews, and the process itself is rarely analysed.

Earlier steps are rarely reviewed to see how the role was defined, how it was advertised, which channels were used, and what kind of expectations were created for candidates.

Shift-left for hiring

In development, shift-left means bringing checks closer to where problems appear. Instead of discovering all issues at the very end, we invest in earlier analysis, earlier feedback, and earlier corrections. The same approach works well in hiring.

The first step is the job itself. Before sourcing starts, the team needs a clear understanding of what kind of work actually exists. No copy-pasting of the job requirements from other teams or, worse, other companies. No “senior backend engineer knowing this and that” but concrete activities prepared during careful job analysis; real work constraints and trade-offs: legacy systems, on-call or not, time zones, stakeholders, level of chaos, growth opportunities, and so on.

The resulting job description (JD) should be then tested.

In software development, we walk through requirements with the team and check whether they make sense, if we understand them the same way, and that they are feasible. In hiring, we can do the following:

- walk the JD through the current team and check whether it corresponds to reality;

- validate it against a current high-performing person in a similar role; ask yourself a question if this person would qualify for the JD;

- show it to trusted people in the network and ask what would make them hesitate or ignore such a role.

Real Job Description not only improves candidate sourcing, but also allows candidates to self-select better.

I recall reviewing JDs in that bank I worked for: they were a standard HR copy-paste. No wonder why candidates weren't even reading them, and we had to interview so many candidates clearly unfit for the position.

Andon cord for hiring

In Toyota’s production system (TPS), workers can pull the Andon cord to signal that something is wrong: for instance, a defect is found. The line can stop until the cause is understood. The principle is simple: do not continue producing waste if there is a clear sign that the process is broken.

If only I had such a cord at that bank's interviews process: stop the interviews after 5 consecutive unfit candidates, and go ask questions, do shift-left testing. I would have saved myself hundreds of hours, and extreme amount of money for the company.

Bringing Andon into hiring means agreeing on clear rules for “bad process”. For example:

- the fifth candidate in a row fails the same interview;

- the third person hired into this role fails probation;

- the second candidate in a row rejects the offer for the same reason;

- more than 50% of candidates do not complete the interview cycle.

Any of these can be a signal to stop. Not to pause for a week and then repeat the same, but to actually go back one or two steps left in the flow and review them. Maybe the job description is wrong. Maybe the sourcing channel brings completely off-profile candidates. Maybe the interview content does not match the actual work. Maybe compensation is clearly out of market.

In hiring, an Andon cord is just a disciplined agreement about when to stop and revise the system instead of just continuing to run it.

Andon is a good signal for immediate shift-left.

Simple charts for hiring

The Andon cord approach assumes a set of “static” rules. However, if we are hiring a lot, as I was in the bank, there will be many variations in the process within a year: sudden market shifts, a local QA or dev upskilling programme finished by 200 people, changes in company reputation, and so on.

These variations may cause our static rules to either trigger too often or not trigger at all, even though the process is behaving as expected for the new conditions. In such a context, static Andon rules alone do not always give clear signals.

Suppose there is an Andon rule: “if 5 candidates in a row fail the technical interview, we stop and review the JD and interview process”.

In “normal” conditions, let’s say the team usually hires 2 out of 10 interviewed candidates for a role, and this is considered acceptable for that market and role. This means that runs of several failed candidates in a row are normal noise.

Now imagine that a local QA "upskilling" bootcamp has just produced 200 graduates, and many of them apply to your mid-level/senior role because the JD looks attractive and they are eager to try.

For several weeks, the team receives a large input of underqualified candidates. As a result, you suddenly see many sequences of 5 failed interviews in a row. The static Andon rule fires multiple times. Each time it fires, the team stops, reviews the JD, reviews the interview process, and sees no internal change: the process, questions, and expectations are the same. The only real change is in the inflow of candidates.

In this situation:

- the static Andon rule causes repeated “false alarms”;

- the team wastes time on reviews that do not lead to useful adjustments;

- interviewers become "desensitised" to Andon signals and start ignoring them.

If, instead, the team tracked simple control charts, the picture would look different. For example:

- a weekly chart of “interview → pass” rate would show a temporary drop during the bootcamp wave, then a return to the usual range;

- the values would still be inside statistically expected boundaries for this role and market;

- the pattern would be recognised as a short-term, external variation, not necessarily as a defect in the internal process.

The team could then decide on a more appropriate response, such as temporarily filtering for experience level earlier, or adjusting sourcing channels, instead of repeatedly reworking the JD and interview kit that are already adequate for the intended target group.

Control charts in this case do not replace Andon rules, they complement them. Andon gives immediate, local “stop” signals; charts show whether a series of such signals is part of normal variation or indicates a real process shift that requires redesign.

Conclusion: hiring as a QA responsibility

The hiring process determines who joins the team, how long they stay, and how they contribute to the product. The quality of this process directly influences the quality of the product and the effectiveness of the team. Treating hiring as a vague, intuition-driven activity and treating interviews as a necessary burden leads to the same outcomes as software development without clear requirements, feedback loops, or quality controls: high waste, rework, and frustration.

My experience at the bank — around 400 hours of interviews per year and only 35 hires — illustrates what happens when the verification stage absorbs the full cost of upstream flaws. From a QA perspective, this is a system where defects are allowed to propagate and accumulate at the most expensive stage.

Applying QA thinking to hiring does not require large organisational changes. It can start with small steps: clearer role analysis and realistic job descriptions, basic “requirements testing” for those descriptions, explicit Andon-style stop rules, and simple charts tracking key conversion ratios and cycle times. These measures are already familiar to anyone who works with process quality; they only need to be applied to hiring.

Hiring is a process like any other important process in a company. It can and should be analysed, monitored, and improved. For people working in QA, participating in this work is not an intrusion into “HR territory”, but a natural extension of the same responsibility: ensuring that systems, including human systems, produce reliable and efficient outcomes with as little waste as possible.